A First Look at PyPTO. "Tile & Human"

Reference: Article by Zhihu user 风雨携晴

Reference: CANN Public Resources: Documentation, Code

PyPTO’s Core Philosophy: “Human-in-the-Loop”

PyPTO was designed with a clear understanding from the start: the operator optimization process is full of NP-Hard problems, and trying to find the optimal solution through automated configuration search in a short amount of time is unrealistic.

Therefore, PyPTO’s design philosophy is not to “directly solve the problem,” but rather to build a mechanism for solving the problem.

It chose a path similar to hardware RTL development. In the RTL development flow, from timing analysis to place and route, the tools do not attempt to solve all NP-Hard problems. Instead, they provide feasibility judgments and final performance evaluations based on the designer’s (a human’s) experience and constraints.

PyPTO hopes to draw from this model by introducing human experience into the optimization loop, reducing the complexity that users have to face directly and allowing developers to focus on leveraging their professional insights.

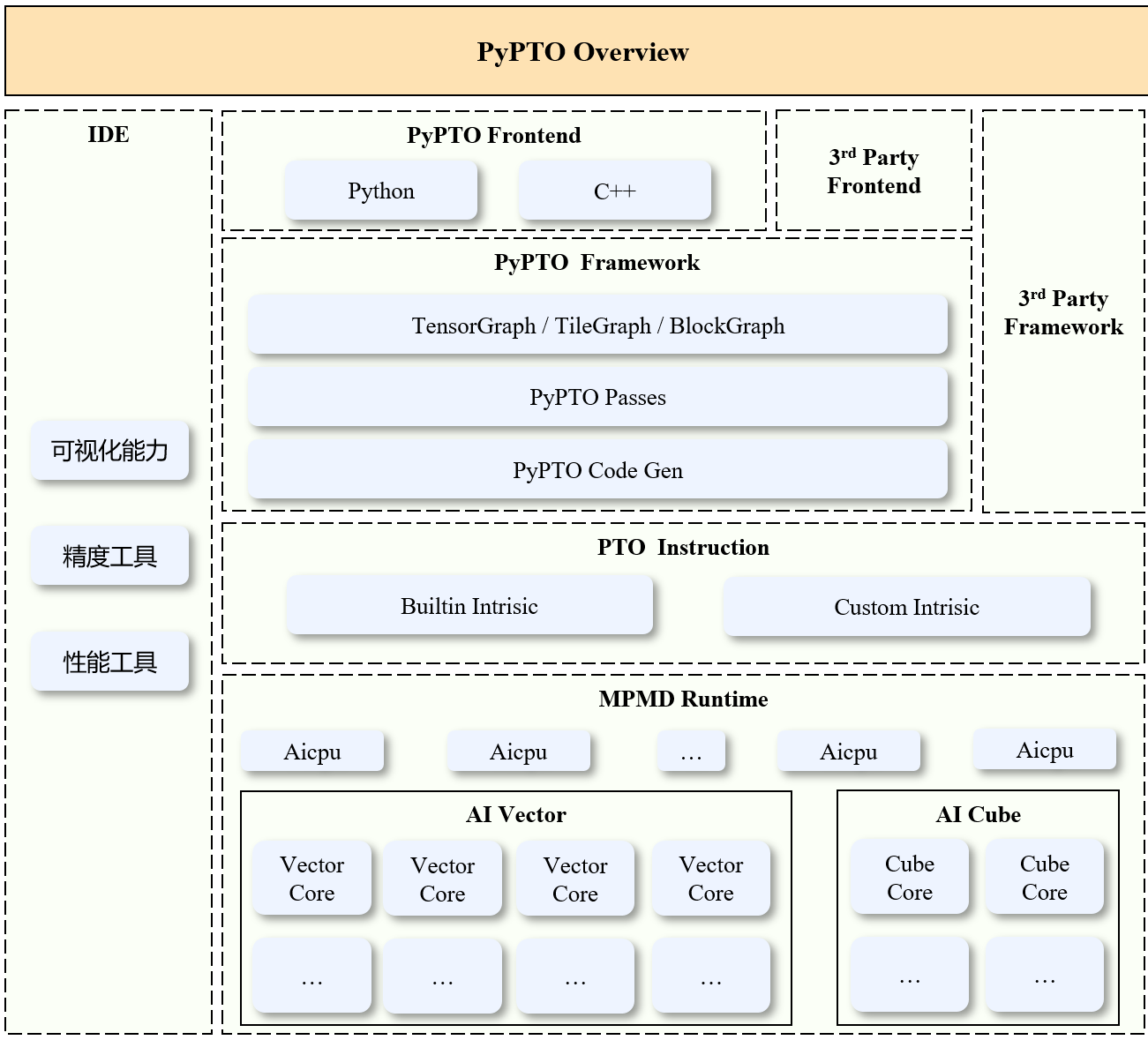

To achieve this goal, PyPTO is centered around on-chip SRAM management, building a white-box toolchain with rich debugging tools and intuitive visualization capabilities.

PyPTO Introduction and Key Features

Motivation

Operator Optimization (Compute/Memory Opt.) -> Operator Fusion (Reduce overhead, expand optimization space) -> New Programming Paradigm (To handle the high complexity brought by fusion)

Ultimately, PyPTO chose Tile as the new programming paradigm to support efficient fused operator design.

Summary of Features

- Automated SRAM Management: It can automatically generate read/write instructions without needing to manually manage SRAM. At the same time, developers can control Tiling partitioning and SRAM utilization strategies through parameter configuration, which is very similar to using

directivesto guide synthesis in HLS. - Abstract PTO (Parallel Tile Operations) Instructions: It defines a set of platform-independent PTO instructions. By implementing these instructions on different hardware platforms, it achieves automatic operator code migration.

- MPMD (Multiple Program Multiple Data) Runtime: Dependencies between tasks are managed at the task level rather than through global synchronization, improving execution efficiency.

Abstraction Layers

PyPTO’s data object abstraction hierarchy is very clear:

Tensor -> [Tiling] -> Tile

Logically, developers only need to care about the computation logic, without needing to be aware of the underlying memory, scheduling, and hardware details. The table below shows some of its core operations (PTO’s O):

| Category | Example Instruction | Function Description |

|---|---|---|

| Element-wise Op | TADD | Performs element-wise addition on two Tile data blocks |

| Tile-Scalar Op | TADDS | Adds a scalar to each element in a Tile data block |

| Axis Op | TROWSUM | Performs a sum operation on each row of a Tile data block |

| Matrix Multiply Op | MAMULB | Performs matrix multiplication on two Tile data blocks |

| Fixed Pipe Op | TMOV | Moves a Tile element from a source register to a destination register |

| Memory Op | TLOAD / TSTORE | Loads data from memory to a Tile or stores it back |

| Complex Op | TCVT | Performs type conversion on a Tile data block |

Core Mechanisms: Tiling Management and Human-In-The-Loop

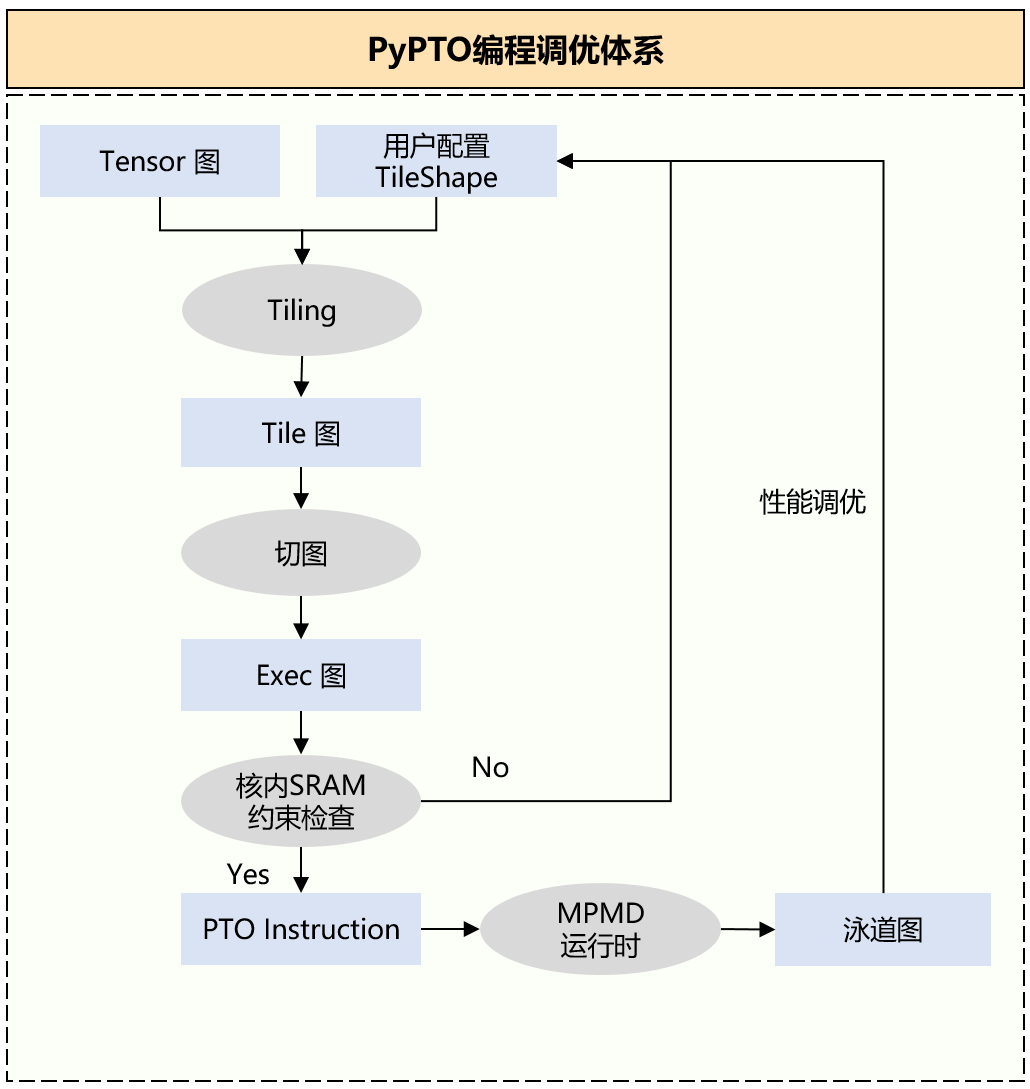

Tiling Management

PyPTO provides two ways to manage Tiling:

- Framework-Built-in Tiling: By setting the

Tile Shapeparameter, the framework automatically expands the Tensor computation graph into a Tile computation graph. - Custom Tiling: Users can define their own partitioning of the Tile computation graph and manually insert data movement instructions.

The inputs and outputs of each partitioned subgraph (Kernel) are in Global Memory, while the subgraph internally uses only on-chip SRAM. This partitioning is a complex trade-off process that needs to consider operation affinity, subgraph isomorphism (to improve reusability), and subgraph-level parallelism.

Human-In-The-Loop Optimization Approach

The entire process, from operator description to final execution on hardware, involves multiple stages such as Tile expansion, graph partitioning, and runtime scheduling. Many of these stages face NP-Hard problems, making it unrealistic to rely entirely on the framework to automatically generate optimal solutions.

Therefore, human participation becomes crucial. PyPTO’s approach is to provide the necessary interfaces to allow users to participate in this optimization process. Tiling management is one area where users can intervene, but what about graph partitioning and runtime scheduling? This is a very interesting question in PyPTO’s design.

Code Example: DeepSeek Indexer Prolog Operator Analysis

Next, we’ll dive deep into PyPTO’s programming practices through an example of a fused operator, Indexer Prolog. This operator is the first half of the Attention calculation in DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp, and its core value lies in:

- Fast Filtering: Efficiently computes similarity scores between a Query Token and all historical Tokens.

- Quantization Acceleration: Significantly reduces computation and memory usage through W8A8/A8/C8 quantization.

- Outlier Suppression: Uses the Hadamard transform to improve quantization accuracy.

You can find its implementation in this repository.

Overall Structure

-

.hfile: Defines the operator contract (input/output) and Tiling configuration (declarations only). -

.cppfile: Implements the IR construction logic (compile-time metaprogramming).

.h File: Operator Contract and Configuration

The role of the header file is very clear:

- Compile-Time Interface: Declares the Shape, Type, and Layout of the operator’s inputs/outputs to the compiler.

- Performance Configuration Table: Centralizes all Tiling-related parameters to support AutoTuning.

// quant_lightning_indexer_prolog.h

// 1. Tiling and performance-related parameter configuration

struct QuantIndexerConfigs {

// Tile params

std::array<int, TILE_CUBE_DIM> qLinear;

std::array<int, TILE_CUBE_DIM> qHd;

// ... other parameters ...

// Config params

std::set<int> unrollList = {32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1};

int cycleUpperBound = 8192;

// ...

};

// 2. Input/Output Contract

struct QuantIndexerPrologInput { const Tensor &x; ... };

struct QuantIndexerPrologOutput { Tensor &qInt8; ... };

// 3. Function declaration (for compile-time linking)

void QuantLightningIndexerProlog(...);

.cpp File: IR Construction (Compile-Time Metaprogramming)

The core purpose of the .cpp file is to construct the Intermediate Representation (IR) of the computation graph, not to execute the computation.

Operator Entry Point

The QuantLightningIndexerProlog function is the operator’s entry point. It is responsible for registering the function and orchestrating the computation flow.

// Operator Entry Point

void QuantLightningIndexerProlog(...) {

// Set Machine Global Config, such as scheduling policy

config::SetRuntimeOption("machine_sched_mode", ...);

// Register the function and declare inputs, outputs, buffers, etc.

FUNCTION("QuantLightningIndexerProlog",

{inputs.x, inputs.qNorm, ...}, // Inputs

{outputs.qInt8, outputs.qScale, ...}, // Outputs

{...}) // What are these?

{

// Call the core computation graph construction logic

QuantLightningIndexerPrologCompute(inputs, outputs, attrs, configs);

}

}

Operator Construction (QuantLightningIndexerPrologCompute)

This function is the real core. It uses the APIs provided by PyPTO to declaratively build the computation graph.

void QuantLightningIndexerPrologCompute (...) {

// 1. Set Pass options, this is the core interface PyPTO provides for manual optimization

config::SetPassOption("nbuffer_merge_mode", 0);

// ...

// 2. Get Tensor metadata

DataType xDtype = inputs.x.GetDataType();

SymbolicScalar t = GetInputShape(inputs.x, 0); // Get dynamic axis

// 3. Create new Tensors based on metadata (for intermediate computations)

Tensor wQb(..., "wQb", TileOpFormat::TILEOP_NZ);

// ...

// 4. Define the computation logic (in a loop)

// This is a compile-time loop that will be unrolled during compilation

LOOP("QuantIndexerPrologLoop", ..., unrollList) {

for (int unrollLength : unrollList) {

UNROLL(unrollLength) {

// 5. Manually set the Tiling Shape

// Note: Tiling here is not fully automatic; developers need to set it manually

TileShape::Current().SetCubeTile({qLinear[L0M_INDEX], ...});

// 6. Construct a computation graph node

auto qS32 = Matrix::Matmul<...>(DT_INT32, qNorm, wQb);

// 7. You can also call functions to construct subgraphs

std::tuple<Tensor, Tensor> qRes = PrologQuant(qHadamard);

// 8. Write the final result back to the output Tensor

Assemble(std::get<0>(qRes), ..., outputs.qInt8);

}

}

}

}

Summary of Core Concepts

From this code analysis, we can draw several core conclusions about PyPTO:

- Declarative Programming: The code in the

.cppfile does not execute computations but instead returns IR AST nodes (like thePrologQuant()function). - Compile-Time Loops:

LOOP/UNROLLare compile-time directives used for code expansion and generating different Kernel versions, not runtime loops. - Explicit Optimization: The operator optimization process, such as Tiling and passing pass parameters, is done explicitly in the code.

Thoughts and Discussion

PyPTO is undoubtedly an EDSL similar to Chisel (for hardware design) and Halide (for high-performance computing). Its .cpp file is essentially for constructing a computation graph, and it has strong characteristics of a schedule language, but it doesn’t seem to pursue a strict logic-scheduling separation like Halide (which is a design choice worth discussing in itself).

Looking at the operator construction code, apart from Tiling which requires deep user involvement, tasks like graph partitioning, mapping, scheduling, and concurrency are all handled automatically by the compiler/runtime. At this level, the programming abstraction provided by PyPTO is quite high, similar to Triton.

However, the amount of boilerplate code in practice still seems a bit high, which might be an inherent challenge of the C++ EDSL approach. A point of critique here is, isn’t it called PyPTO? Why is everything written in C++?

But this is not the core issue. I believe the essence of a programming language’s design lies in its abstraction layer. PyPTO has chosen a high level of abstraction, and its greatest challenge is: how to design the interaction mechanism between the user and the compiler to truly achieve a human-"HAPPY"-in-the-loop and bring out the effectiveness of the “white-box” toolchain.

Is the config::SetPassOption seen in the code the best way to do this? This remains to be seen with further experimentation. But for now, I haven’t gotten an environment where I can run this. I will provide updates later.